Brexit: The Students’ Guide

If you’ve ever found yourself wondering what on earth a Brexit is, or been left frustrated by news articles that assume an existing level of knowledge on the subject, then this is the post for you! We’ve put together the ultimate students’ guide to Brexit, covering everything from why it’s taken so long, to how it could affect students in the coming years.

What is ‘Brexit’?

The word ‘Brexit’ is a combination of ‘Britain’ and ‘exit’. It’s the process of Britain, also known as the United Kingdom (UK), leaving the European Union (EU). The UK includes England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland.

Brexit has caused a huge amount of debate and controversy because it will probably affect trade, security, and UK immigration. In June 2016, the UK voted to leave the EU in something called a referendum. This is a general vote where a country’s entire electorate is asked to weigh in on a single question, and the result directly influences the decision of the government.

What is the EU?

The European Union (EU) is a group of 28 countries in an economic and political union. It allows free trade and movement of people across all of its member states. A single market was created to increase trade between countries, leading to more jobs and lower-priced goods.

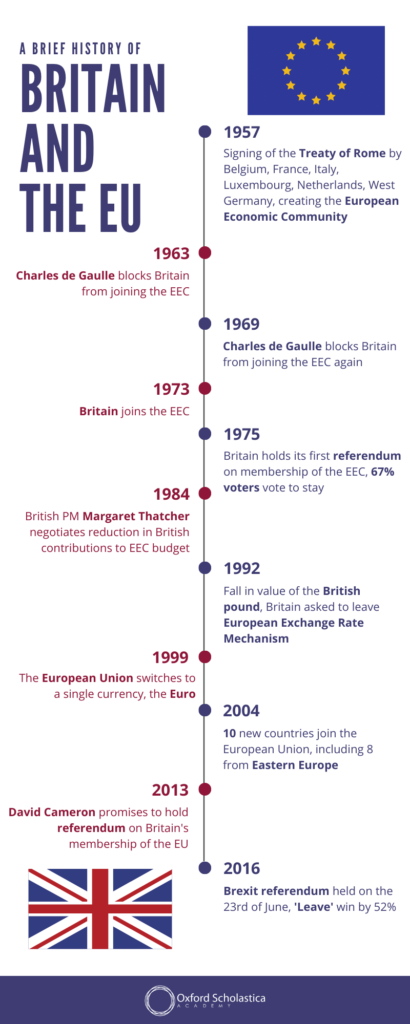

The EU was born from the legacy of World War II. Countries believed that if they were linked economically and constantly cooperated, then they were less likely to go to war. This led to the creation of the European Economic Community (EEC), founded by the Treaty of Rome in 1957 and signed by Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and West Germany. Britain applied to join the EEC, but the French president Charles de Gaulle vetoed its application in 1963 and 1969.

The UK finally joined the EEC in 1973 under the Conservative government of Ted Heath, but even then its membership was debated. In 1975 the UK held its first referendum on its EEC membership. The Labour party was now in government, and it was divided over the issue of Europe. The new Prime Minister Harold Wilson promised to put the question to a referendum, and 67% of voters wanted to stay.

However, the role of the UK in the EU continued to be debated. Conservative Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher argued from 1979 that the UK was contributing too much to the EU budget. In 1984, Thatcher negotiated a reduction in British contributions to the EEC budget, called the ‘rebate arrangement’.

In 1992, the British pound sterling fell in value so much that Britain was asked to leave the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM). The ERM was a system introduced by the EEC in 1979, to reduce the fluctuation of exchange rates between European countries. The aim was to achieve monetary stability, which was a step towards creating a single currency, the Euro. Britain never adopted this, but most of the EU started using it in January 1999. In 2004, ten new countries joined the EU, including eight from Eastern Europe, which saw an increase in EU citizens moving to the UK.

How did the Brexit vote happen?

The Brexit referendum

In 2013, the UK’s Conservative Prime Minister, David Cameron promised to hold a national referendum on the UK’s EU membership.

He argued that the British people were disillusioned with the EU and that they should have a direct say. This took place in a context of economic uncertainty, just six years after the financial crisis of 2007-2008. Cameron believed that he could renegotiate the UK’s relationship with the EU, so he could give the British people a choice between staying under new terms, or leaving completely.

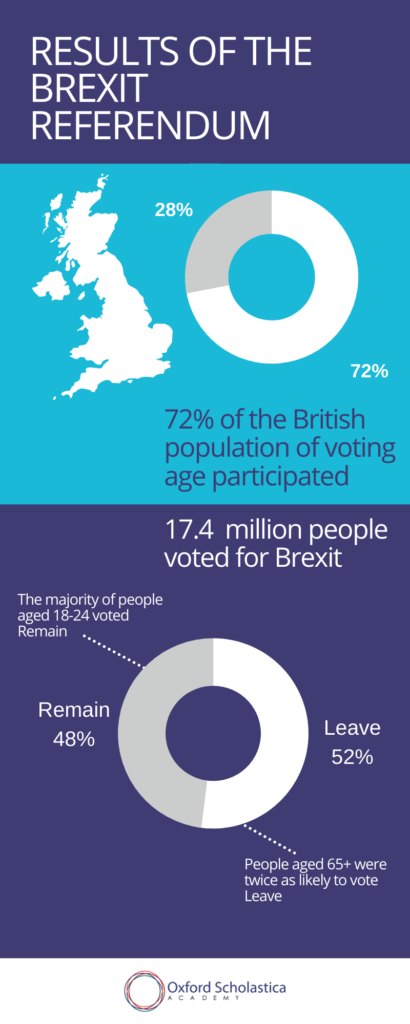

Britons were asked to choose whether they wished to ‘Leave’ or ‘Remain’ in the EU. A Leave win was unprecedented; no country has ever fully left the EU before. 1985 saw Greenland leave, but it is within the kingdom of Denmark, which remained. The Brexit referendum was held on Thursday the 23rd June 2016. Voter turnout was 72.2% of the British electorate, with 52% voting leave and 48% choosing remain. Find a more detailed breakdown of the results here.

Why did people vote ‘Leave’?

The Brexit referendum took place in the context of a refugee crisis in Europe, making migration levels a key issue at the time. To Brexit supporters, the prospect of leaving the EU was a promise to end the free movement of people into the UK and decrease the number of people moving here.

Pro-Brexiteers claimed immigrants put too much pressure on public services in the UK, such as the National Health Service (NHS) and social welfare schemes. Many people disliked the way the European Parliament decided on rules the UK had to follow and wanted the UK to have more control over its own affairs.

Several different political organisations campaigned for the Leave vote. The UK Independence Party (UKIP), led by Nigel Farage, carried out an aggressive campaign based on anti-immigration views. It was not, however, affiliated with the official Vote Leave campaign, which included Boris Johnson and Michael Gove, amongst other key politicians.

The Vote Leave campaign was accused of breaking election laws and having used outright lies to sway the electorate. Johnson, one of the foremost players in the Leave campaign, organised a bus painted with the slogan: ‘We send the EU £350m a week: let’s fund our NHS instead’. It was later proven that this figure was false, but it did motivate some people to vote Leave.

Why did people vote ‘Remain’?

Many of the 48% of the British population who voted ‘Remain’ argued for the business benefits of being in the EU. They believed the single market system was good for the British economy, bringing in immigrants to develop the British workforce and public service projects. They also thought that being members of a wider economic and cultural community provided an element of security. The majority of people between the ages of 18 and 24 voted Remain. People over the age of 65 were more than twice as likely to vote Leave.

When did Brexit happen?

The UK officially left the EU at 11pm on Friday 31st January 2020. This marked the beginning of a “transition period”, which will last until the end of 2020.

In reality, the transition period means not much will actually change until 2021, when trade, travel and businesses will have to fall into line with post-Brexit legislation.

Why did Brexit take so long?

It has taken over three and a half years for Brexit to actually happen. The main problem is the lack of precedent; since no other country has officially left the EU before, no one really knew how this was supposed to happen.

Some people also argued that a second referendum should be held, since many were uncertain about what Brexit meant in 2016. False information was used in campaigns both for ‘Leave’ and for ‘Remain’, and ‘what is the EU’ Google searches peaked in the hours after the results of the vote were announced.

What are the different kinds of Brexit?

The exact nature of Brexit is still relatively unknown. The current agreement is really just an extension, meaning politicians are still trying to work out the bounds of the “real” deal, which will set legislation on trade, travel and our political relationship with the EU.

‘Deal’ or ‘no-deal’ Brexit?

A ‘deal’ Brexit is what many people are hoping for. This would mean the UK and the EU reach an agreement before Britain leaves, ideally preserving trade links and the customs union until a more detailed relationship is worked out.

A ‘no-deal’ Brexit is what would happen if the UK leaves the EU without this agreement. In this case, the UK would leave the customs union and single market overnight. EU checks on UK goods could lead to delays at ports, increased traffic, and a fall in the value of the British pound.

‘Soft’ or ‘hard’ Brexit?

A ‘soft’ Brexit would see Britain remain close to the EU and keep some form of the EU’s single market. This option would minimise economic disruption. The main sticking point with this is the EU’s insistence that access to the single market will only be granted if free movement of people into the UK is accepted too. As immigration was one of the cornerstones of the Leave campaign, politicians have been reluctant to accept this compromise.

A ‘hard’ Brexit means a clean break from Europe. Britain would give up its membership in the EU’s single market and customs union entirely. Supporters of a hard Brexit want freedom for the UK to draw up its trade deals and rules.

Attempts at a Brexit deal

Undoing 46 years of economic integration is not simple. Officially Brexit was supposed to happen on the 29th March 2019, two years after the Conservative Prime Minister Theresa May triggered Article 50, beginning the formal process of leaving the EU and kicking off negotiations. While May was PM, this deadline was delayed twice. For her Brexit deal to pass, she needed the approval of Parliament, but members of the British Parliament (MPs) repeatedly rejected the deals she presented. Parliament’s opposition pushed May to resign in July 2019, and she was replaced by Boris Johnson as leader of the Conservative Party and Prime Minister.

On the 19th October 2019, Johnson tried to put forward a new Brexit deal but this was also denied by MPs. He was forced to request another delay from the EU, with the new deadline for a Brexit deal being the 31st January 2020. After Parliament blocked his deal, Johnson called another general election, on the 12th December 2019. His aim was to achieve a Conservative Party majority, and he was successful.

Key issue: the Irish backstop

The main reason May’s successive deals were not voted through was the issue of the Irish border ‘backstop’. This is a special policy in May’s deal that addresses the how Brexit will affect the Irish border.

Northern Ireland is part of the UK and governed by the British Prime Minister, while the Republic of Ireland has its own head of state and government. As part of the UK, Northern Ireland is set to leave the EU, while the Republic will remain a part of it. Currently, they have an ‘open border’, meaning people and goods can cross it freely. This was a condition of the last peace agreement, which saw the historic conflict between the two states cease. Creating a new ‘hard border’ threatens a renewal of hostilities on this front.

May’s attempted deal aimed to keep the UK and EU linked in a trading relationship, so customs checks would not have to take place at the Irish border. Critics argued that this could prevent the UK from making trade deals with other countries.

Boris Johnson’s new withdrawal agreement did not include a backstop, which he called ‘anti-democratic’. His own plan for customs arrangements would allow the UK to sign trade agreements with other countries. It would also have led to a customs and regulatory border between Northern Ireland and Great Britain. This agreement was opposed by the Democratic Unionist Party of Northern Ireland (DUP) as it would economically separate Northern Ireland from the rest of the UK. This was problematic for the Conservative Party as the DUP had previously been one of its major sources of support.

What happens next?

Prime Minister Boris Johnson won the general election on the 12th December 2019. This vote was heavily influenced by people’s views on Brexit. The four largest political parties currently in Parliament are the Conservatives, Labour, the Scottish National Party (SNP) and the Liberal Democrats. The results of the vote mean that the Conservative party, led by Boris Johnson, will continue to head up the Brexit plans.

Another referendum?

Labour, the main opposition party, were very critical of Johnson’s deal and plans for Brexit. Led by Jeremy Corbyn, the Party said they would put it to a second referendum, or ‘People’s Vote’, if they were elected. The Liberal Democrats campaigned to stop Brexit immediately if they were voted in. Technically, the UK could have revoked Article 50 and reversed Brexit, as the European Court of Justice has ruled this would be legal. However, following the results of the general election on the 12th December and the passing of the European Union Withdrawal Agreement Act 2020, a second referendum forms no part of the government’s plans.

Consequences of Brexit on a global level

The extent of the impact Brexit may have on an international level depends on the kind of deal with which Britain leaves the EU. The UK has the fifth biggest economy in the world. Brexit could lead to political and economic uncertainty, which would negatively impact the world’s markets. The Great British Pound has significantly lost value against the Euro since the Brexit vote.

How does Brexit affect students?

Many academics fear that Brexit could cut research funding from Europe, make exchanges with European academics more complicated, and lead to a decline in students from the EU studying at UK univiersities. In 2014 EU students represented 5% of university enrolments, and supported more than 34,000 jobs. EU students are currently treated as domestic and pay the same yearly fees as their British counterparts, rather than the higher amounts paid by those coming from further afield. Brexit could also lead to the loss of Erasmus funding for academic exchange across the EU, which has been in place since the 1980s.

For international students, it’s currently cheaper to visit the UK right now due to the fall of the pound. Brexit’s unknown impact on the global financial market means we don’t know how much it will impact students internationally in the long run. However, the current Conservative government is considering plans to limit student immigration.

Key takeaways

Brexit is complex, and almost impossible to predict. Much of the debate around it stems from the fact no one really knows what will happen if and when it goes through. Polls show that, even three years after the initial vote, the country is still divided.

While we can’t predict the future, we do hope our guide has made the process of Brexit so far easier to understand. Keep an eye out for updates as the transition period progresses!

- Keep up to date with Brexit news and the EU referendum.

- Interested in Politics and International Relations, Debate or Law? We’ve got the summer school for you! Learn about our top summer programmes for teens:

- Interested in becoming a Politician? Read our blog How to become a Politician!

Seriously considering a career in Politics?

Take your political understanding to the next level with an Oxford summer course in International Relations, Politics and Leadership.