Preparing Students for Future Jobs

All of this occurs in a backdrop where the very essence of how to prepare for the future of work is changing. Economic and ecological stability can no longer be taken for granted. The rules that once promised a comfortable suburban reward no longer apply, as the world that delivered those rewards has evolved. Despite these challenges, we continue to build for our future because that’s what it means to shape the world we inhabit.

As D.H. Lawrence wrote: “There is now no smooth road into the future: but we go round, or scramble over the obstacles. We’ve got to live, no matter how many skies have fallen.”

Does school prepare students for the future?

The worst way to value your education is by thinking of it solely in terms of what it gets you. If we tell students to go to school so that they can obtain a job, we are telling them that education is a means to an end. And, of course it is – to a point. But are we suggesting that if that student had enough money, school would become obsolete, and s/he would no longer need an education? We have turned going to school into a token economy. And that token is a career, which itself has become a token for security and comfort. But no token will buy your passion. When was the last time you were excited to enter a classroom? And if you never were, when will be the first time you are excited to go to work?

When careers were based on obedience, acquiescence and predictability, schools churned out students like cogs to keep the machinery of the economy running. Businesses were thought of as things. People were things that made things, or things that bought things. The consumer-producer was, ironically, the ultimate product of society. Children had a sense of what work would be like based on watching their parents – their job was to become what they saw, become what shaped them. The relationship between school and work was based on the emulating relationship of child and parent.

Now, businesses are understood as dynamic entities, and the people comprising them are thought of as rich resources of growth who are expected to create, not only obey. Now, children are raised not merely to obey their parents but to grow, to think and to choose for themselves. Now, it is not precedence but creativity that is valued. If the world of work has changed, has the world of education led the way – or has it even caught up? Schools largely do not fit the needs of the world, both as it is and as it is becoming. That is because such schools largely do not exist.

I work at one of the few that does.

The future of education and skills education

Indeed, the American presidential election has taken up this theme. Andrew Yang, a Democratic candidate and entrepreneur, has pointed out that about 10 million jobs related to truck driving will disappear this generation as autonomous cars play a burgeoning role in the economy. That would be akin to the entire population of London losing its job. We are giving students a prescribed route to a future that will never arrive. Similarly, Republican President Trump is attempting to negotiate a new trade deal with China in which innovation and intellectual property are given greater precedence so as to protect creativity and inventiveness.

The most devastating critique of schools I read when I attended school was that their main function was not in fact to educate, but to train. Students were trained to enter and endure a hierarchy, obey an authority figure, suppress creative drives, fit in or suffer, obey or fail, avoid punishment, pursue rewards, expect a perfunctory progression over the years, and, finally, mercifully, leave. This is precisely the mentality of the old work paradigm.

Hence schools, the critique argues, were not failing to inspire students; they were teaching students how to function without being inspired. The idea of school, then, was to get you used to work before you even started. That way, both seemed normal. By the time a student graduated from university, she or he carried this tragically functional attitude from over a decade of completing tasks that neither provided meaning nor fed passion. Learning how to do this again and again in exchange for material rewards – that was one’s education. Doing nearly everything as a means to an end gave the subtler lesson that each student was themselves a means to an end.

Only a few are expected to think, and so only a few are taught to. As Bill Gates said when he toured Stanford, “I dropped out of the wrong school.” Indeed, the World Economic Forum (WEF) identified these ten skills as the most needed for thriving at work: Problem Solving; Critical Thinking; Service; Communication; Management; Negotiation, Cognitive Flexibility; Creativity; Cooperation; Decision-Making. Not only is none of these a class in the old education paradigm, excelling at them can be more of a hindrance than a benefit.

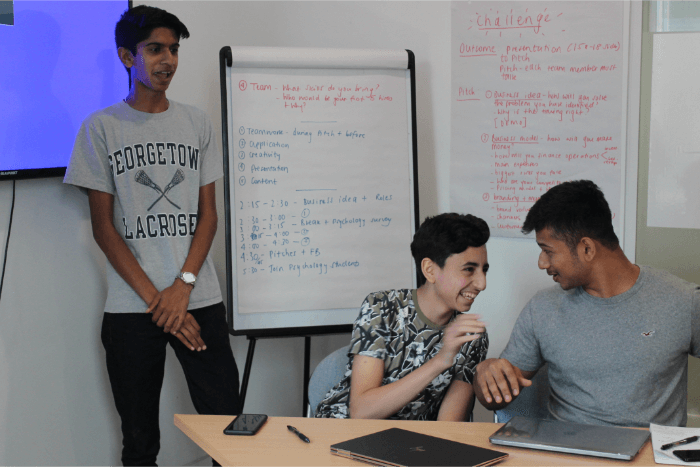

Preparing students for 21st century skills by having classes centred on these skills both creates the kinds of thinkers and innovators the world needs, and brings out the personal connection and meaning students seek. Imagine your class is Cognitive Flexibility and Communication. Your homework is to learn something that changes your mind. Your task is not to emulate what you are told, but to ensure you are not the same person at the end of class. You have to overcome your cognitive dissonance, find the people who disagree with you, and encourage them to eloquently dialogue with you. Instead of learning the status quo and repeating it for the reward of a grade, your task is to change your status quo for the reward of your growth. There is a school that actually does this.

How can schools truly prepare students for success in the workplace of the future?

I have taught classes in wealthy and poverty-stricken schools in the United States. I have taught honours classes and special education. I have taught at Oxford University and in a mental health jail. The only school I have seen that embodies these genuine values is the Oxford Scholastica Academy. Teaching these unique Oxford summer courses allows me to create the kinds of classes I wish I had had as a student.

For example, to teach the values of Negotiation, Cooperation, Communication and Cognitive Flexibility, I designed a Model United Nations peace negotiation depicting Israeli and Palestinian groups, with students cast into roles that challenged their personal views. One student remarked that it was only by leaving his familiar perspective and taking on the one he normally argued against that he was finally able to see what the two sides had in common, and how to meet their mutual needs. He began to understand political science not as a zero-sum game but the basis of a world community in which success and peace are only achieved together.

Embracing the Oxford Summer School way of teaching

You might ask yourself, is an Oxford summer school worth it? Consider that Scholastica embodies the journey where a student learns how their passion becomes their work, not how their work prevents their passion. The jobs of the future involve learning to take on new perspectives, solving problems without direct precedent, connecting with people outside one’s comfort zone and taking on new forms of thought rather than staying with the familiar for its own sake. The most practical thing you can do for your future is to understand that it will not be like the past. It is by learning not what has worked, but what will work that you will not only find your niche, but create it.

Individualized curriculum: The student-centered approach

At the Oxford Scholastica Academy, not only do I integrate students into the curriculum, they are the curriculum. Hence we do not ‘teach to the test’ – we teach to the student. Rather than impose a predetermined curriculum on the student before knowing him or her, we integrate student strengths, goals and interests into the class design. Students fill in a questionnaire, give feedback to instructors and receive individualized tutelage based on their interests and learning styles to help them, in Nietzsche’s words, become who they are.

Modern teaching methods: beyond traditional classroom boundaries

Rather than have students learn the cookie-cutter prose of the standard five-paragraph-essay, I have students role-play difficult conversations between themselves and their parents to develop expressive and receptive communication skills. Rather than ask them to memorise the terms of Marxism and Keynesian economics, I have them argue how to end homelessness while only utilising arguments of compassion, or, alternately, while only using economic ones. Whereas some students subscribe to the enlightened self-interest of neoliberalism, others learn to apply the ‘pink tide’ as a counter. It was by combining our opposite approaches that we learned to enrich each other. Combining inner passion with real-world experience keys my students onto making their mark in the world. This is how we stand apart from other Oxford summer schools.

Practical life skills: Preparing students for the real world

When my students completed my courses, they had greater clarity as to what they wanted in a career as well as what they could offer. They had a better sense of how to write meaningful personal statements or engage in university and college admission interviews based on conveying what they wanted to explore and achieve in their field, not just claim that their CV (curriculum vitae) was ‘enough’. To know what makes you special, you have to know who you are. When Socrates says that the unexamined life is not worth living, it is one’s own life that renders the examining. We have asked our students to turn their lives into grades and test scores for too long; we are entering an age where the next generation matters to universities and employers not for what they achieved under the old paradigm but how they’re going to create within the new one.

About the Author: Mitch Artman, a 3rd generation teacher, attempts to create the classes he wishes he had attended as a student. He teaches psychology, sociology, public speaking, political theory and literary theory. He lives in Oxford with his wife and twin daughters.

Want to know more about our inspirational summer courses?

Read more about the Oxford Scholastica experience here.